In awe and resolve, by Anita Higgins, Garden Steward

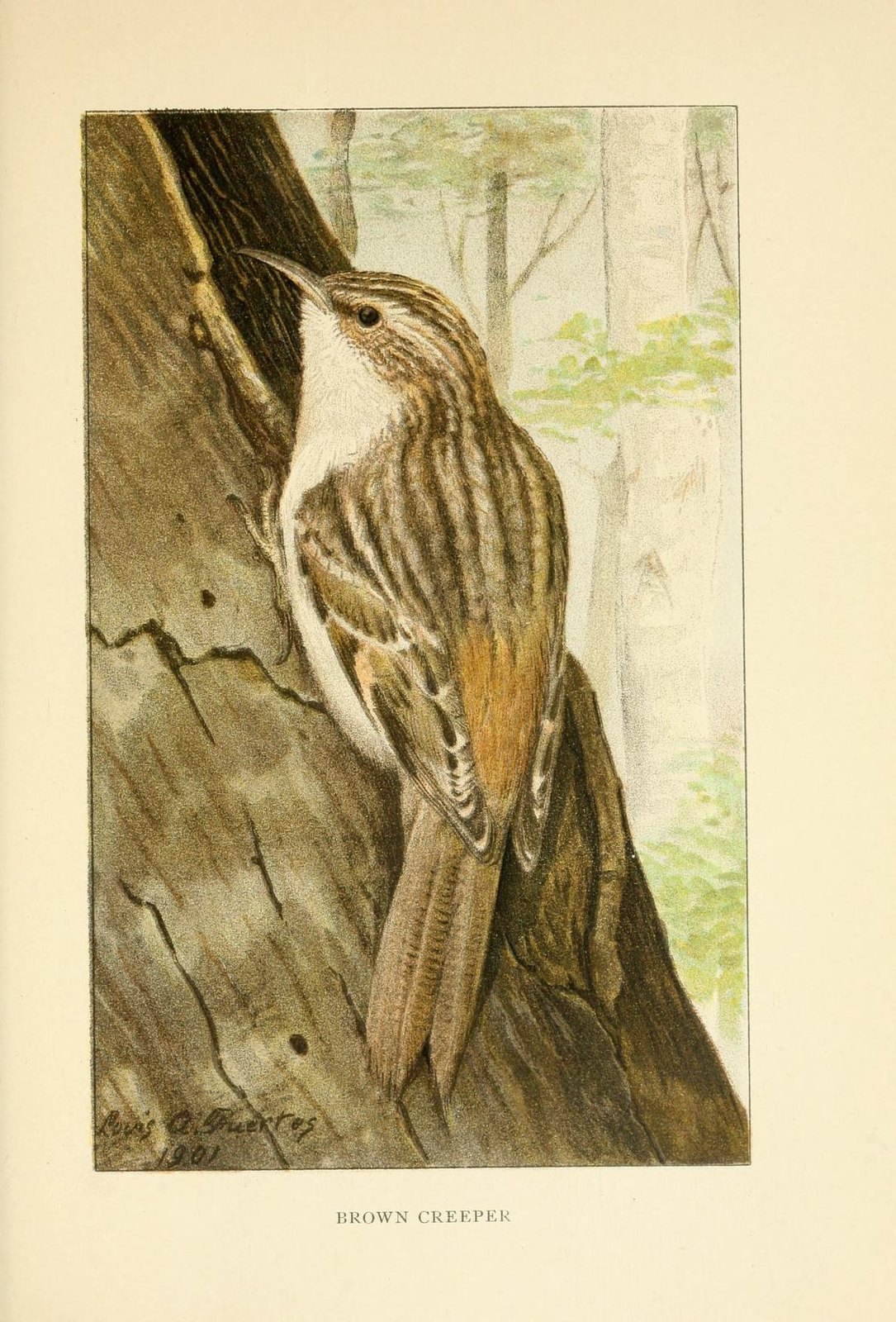

I moved my bed closer to the window last night. It seems that I rearrange my room with the seasons. It hasn’t been intentional, but I’ve noticed that it’s been a pattern. And now I wake up to the early sunlight of these lengthening days, and to the scratching of the brown creeper that’s come, year after year, to build their nest in the cedar siding outside my bedroom window. I should say, the brown creepers that have come to build their nest, as they nest in pairs. Has it been the same creepers every year right outside my window? What of their offspring? Wikipedia told me this morning that brown creepers usually build hammock-like nests under loose flaps of bark on Douglas fir (čəbidac, Pseudotsuga menziesii) snags. Apparently, in human dominated landscapes, cedar siding makes a cozy nesting spot. In April, just as the native vine maple (t̕əqt̕qac, Acer circinatum) below my window starts to think about leafing out, the female creeper will lay 3-5 eggs that both the male and female will care for.

The vernal equinox was last week. Forestry sticks and PoMac (aka "Pojar") in hand, winter intern Ian Thompson and I ventured out into the Songaia woods for a forest field day. Like the nest-building of the brown creeper, one of the first signals of Spring in the Pacific Northwest can be seen in the Songaia forest, as the Indian plum (cəx̌ʷadac, Osmaronia cerasiformis) lights up the understory. Our intention was to get the forest “stand map” established-- the distinction between different stands being where notable changes in environmental conditions or species composition occur. The conditions within these stands will inform our short and long-term stewardship plan in different parts of the forest.

Most of the morning Ian and I wandered the northern half of the forest, noting where the swordfern (sx̌ax̌əlč, Polystichum munitum)-dominated understory slowly transitions to Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium)--and how to distinguish Oregon grape from English holly (Ilex aquifolium). We noted where the forest starts to thin near the Utility R.O.W as the red alders (sək̓ʷəbac, Alnus rubra) begin to age-out, and how this increase in sunlight encourages Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus) establishment.

After a break to help Nancy and Marilyn unload the groceries from one of the community’s weekly shopping trips, we headed back up into the forest. We had spent the morning cultivating an intimacy with the Northern half of the forest, seeing it through a scientific lens. As we passed through the septic field in the middle of the forest, we were reminded how our presence in this forest is unavoidable. And how, at this time of year, you can see the houses out of the forest to the East, West, and South, even when you’re standing in the middle.

What felt like a diverse native ecosystem in the Northern reaches of the Songaia forest, suddenly shifted. As we traveled south through the forest, there was a noticeable increase in the coverage by invasive species (opportunistic, introduced species whose presence reduces overall biodiversity and ecosystem function). We found ourselves sitting in the middle of a stand of dead Douglas fir--looming snags that swayed with the wind. I couldn’t help but feel a sadness. The forest felt so small, so vulnerable--the task of writing this stewardship plan, and then implementing it, too monumental. I sat there with my sadness and my overwhelm, among the swaying snags.

In college, I fell in love with the study of ecosystems. Essentially, what I fell in love with was the study of the relationships between the members of the community of life on this planet. In more intact ecosystems we can see how the species within them perform functional roles in relationship with one another--the output of one being is the input of another. Species co-exist in a dance, a cycle. There is a beauty and a magic to it, only enhanced in my mind by learning to know it so intimately through a scientific lens.

In less intact ecosystems, we can see that cycle broken. The study of ecosystems led me to the study of how we as humans are attempting to restore these broken cycles. Ecological restoration is “the practice of renewing and restoring degraded, damaged, or destroyed ecosystems and habitats in the environment by active human intervention and action” (Wikipedia, 2019). I learned how, worldwide, we're seeing ecosystem collapse and the resulting socioeconomic chaos. The deeper I got into the study of this, the more I started to feel that same overwhelm that came up again standing among those swaying Doug fir snags. It felt as if anything we did would just be putting a band-aid on a deeper cultural wound. Because what causes ecological destruction in the first place?

What I have come to believe is that what causes ecological destruction on the scale we’re seeing is ecologically insane human systems--human systems that don’t participate in the dance with the rest of life on this planet, where what we take as inputs is more than we need and what we discard as outputs are not in the form or amount the rest of the community can use. And these ecologically insane human systems are designed from and perpetuate what is at the root of it all--a degraded, damaged, or destroyed relationship between humans and the rest of the community of life on this planet. And that’s a little harder to restore.

How do we create scalable human systems that integrate humans into the ecology of an area in mutually beneficial ways? How do we restore and steward landscapes in ways that also restore humans to their functional role within them? How do we see, and live from, the truth that our well-being is inextricably linked to the well-being of the rest of the community of life on this planet? How do we create a culture for our children where that truth is woven so tightly into our narratives, that to live any differently would be considered insanity? Where can we start? Locally? What does it mean to restore relationship on a local scale? Personally? What does it mean to be in a relationship of reciprocity with a Doug fir? What are the different types of intimacy with place we must explore? How do we honor indigenous ways of knowing the world? How do we look through a scientific lens that doesn’t reduce what’s real to the measurable? What’s the role of story, song, and music in shifting a cultural narrative? How do we learn to notice the nesting pattern of the brown creeper, and watch our own patterns shift with them?

These are questions I hope to hold in years to come, as I work alongside Songaians to restore and steward the remnant forest in our backyard. I now wake up in the same bed, but miles away from where I did in April. I’m overwhelmed with gratitude to say that I now wake up in a living laboratory, where a strongly held intention is to experiment with living into a different narrative than that told in the dominant culture. A narrative where we recognize that our well-being is linked to the well-being of our human and more-than-human neighbors, in an unending reciprocity. Where that intention to experiment--to be life-long learners--is backed up by action and resource allocation. Where members are working to do this while still being immersed-- in their finances, their conditioning, and their location-- in the dominant culture. Where members do so with recognition of, and gratitude for, those who laid the path before us and those who’ll walk it long after 🌱

In awe and resolve,

Anita

Many species in this document were referred to by their common name, their latin “scientific” name, and by their name in Lushootseed, a language in the Coast Salish family of languages. This information was provided by the Tulalip tribes of Washington (link below w/pronunciation).

https://tulaliplushootseed.com/plants/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed