A Cultural Planting - Project Overview

|

The Songaia Native Forest Garden is an experimental bio-cultural restoration project at the Songaia Community in Bothell, Washington on the ancestral lands of the Snohomish, Snoqualamie, and Stillaguamish tribes.

|

Bio-cultural Restoration acknowledges that restoring a relationship of reciprocity between humans and land is essential in the long term regenerative capacity of a project. |

What Wants to Emerge?

At Songaia, if on your birthday you are 65 or over, in addition to asking you what was significant in the last year and what you look forward to in the coming year, we ask you an additional question. What are you going to do this year that you have never done before?

For her 70th birthday Patricia wanted to plant a forest. Sounds crazy? Yes...but for those of us who have journeyed with Patricia for the last 13 years, it wasn't so surprising. During her years as manager of our community garden she had drawn us deeply into Permaculture and regenerative agriculture. We stopped tilling the garden, we buried wood under the garden beds, we listened to podcasts and read books about how to nurture the soil. We asked the question ...what wants to emerge?

For her 70th birthday Patricia wanted to plant a forest. Sounds crazy? Yes...but for those of us who have journeyed with Patricia for the last 13 years, it wasn't so surprising. During her years as manager of our community garden she had drawn us deeply into Permaculture and regenerative agriculture. We stopped tilling the garden, we buried wood under the garden beds, we listened to podcasts and read books about how to nurture the soil. We asked the question ...what wants to emerge?

|

One portion of our land here at Songaia is know as "the meadow" - a large section of the property that is covered with grass (and giving way to blackberry). Patricia wanted us to turn a portion of that meadow into a "Miyawaki" forest.

Akira Miyawaki was a Japanese botanist and an expert in plant ecology who specialized in seeds and natural forests. He was active worldwide as a specialist in natural vegetation restoration of degraded land. |

|

The mini-forests he promoted are essentially a densely planted area of native plants. The unique quality of this style of forest planting is that they grow much more quickly than natural forests and become self-sustaining in three years. The Miyawaki method is fast becoming a best practice in the regenerative world.

Patricia was suggesting that we plant a Miyawaki forest in the meadow. |

|

But an idea is just an idea until it gains energy and momentum from other directions and begins to emerge.

A Collaboration with the NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service)

An early collaboration that emerged was with the NRCS, which is a section of the USDA tasked to promote conservation practices. After a visit and a nudge from Snohomish County NRCS Resource Conservationist Joshua Hall, we applied to the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). This program works with farmers to give financial and technical support for conservation practices they’re already doing on their land and for conservation “enhancements”, which allow farmers to take a step further into conservation activities beyond what they’re currently doing.

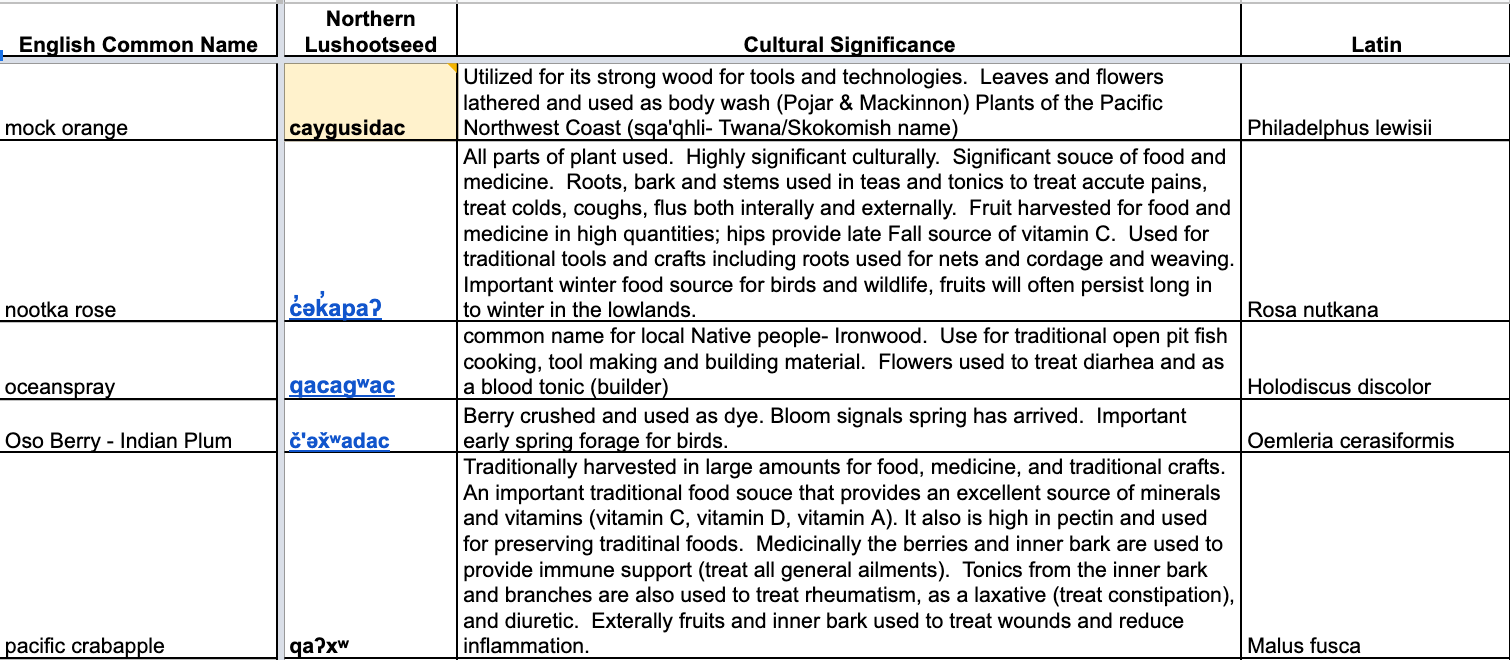

When we reviewed the list of “enhancements”, of which there were over a hundred, we were drawn to one titled “Cultural Plantings”. This enhancement asks the farmer to introduce plants of cultural significance to the indigenous people of their region to a portion of their “pasture” land. It asks farmers to plant species from a list of around 15 native plants that have been approved by a local indigenous consultant, and to plant at a maximum of 10 feet on center.

Meanwhile, Patricia was dreaming of planting a forest in the Miyawaki Method, which requires a diversity of plants to be planted densely in order to achieve the complexity of relationships that allow plantings in this method to thrive.

When we reviewed the list of “enhancements”, of which there were over a hundred, we were drawn to one titled “Cultural Plantings”. This enhancement asks the farmer to introduce plants of cultural significance to the indigenous people of their region to a portion of their “pasture” land. It asks farmers to plant species from a list of around 15 native plants that have been approved by a local indigenous consultant, and to plant at a maximum of 10 feet on center.

Meanwhile, Patricia was dreaming of planting a forest in the Miyawaki Method, which requires a diversity of plants to be planted densely in order to achieve the complexity of relationships that allow plantings in this method to thrive.

|

We needed to expand the list of plants in order to achieve the diversity necessary for the Miyawaki method.

|

Diversity creates the environment for complex relationships to emerge. Those relationships are the foundation for resilience and abundance. |

Restoration of Relationship

“Being naturalized to place means to live as if this is the land that feeds you, as if these are the streams from which you drink, that build your body and fill your spirit. To become naturalized is to know that your ancestors lie in this ground. Here you will give your gifts and meet your responsibilities. To become naturalized is to live as if your children’s future matters, to take care of the land as if our lives and the lives of all our relatives depend on it. Because they do.” |

In her time studying ecological restoration at UW Bothell, Anita observed a pattern that would go on to influence her ways of thinking about land stewardship, and the course of this project. Restoration projects that had the most success—where diversity, function, and resilience were all enhanced and maintained over time—were the projects in which a community of humans had developed a relationship with the site. She observed this in places like the UW Bothell Wetlands, where the communities of students, faculty, and groundskeepers participate in stewardship. The success of that 50-acre wetland restoration project hinges upon the continued care, resource allocation, and experimentation done by the surrounding community. This can also be observed in the 64-acre North Creek Community Forest, in which the surrounding community is involved in regular stewardship. Where human relationship has been restored to the land, the land responds.

|

At the same time, she was learning about how our global human systems have been created through the domination of land and people. In the past few centuries, these systems have created a hierarchy that places only certain humans above all other beings. This hierarchy, which is antithetical to the reciprocal nature of other natural systems, is causing the destruction of the Earth—primarily through divorcing us from the ways of fostering human culture that is in reciprocal relationship with natural systems rather than reinforcing an unnatural hierarchy of control.

|

These systems have become so globalized, so normalized that it’s easy, in the western world, to lose touch with the truth of our interdependence. Many of us have lost touch with any ancestral memory of a different way of relating to the Earth. It is imperative that as old systems of domination are faltering, we look to those communities who still hold cultural memory of being in a relationship of reciprocity with the land and one another. In this part of the Pacific Northwest, that means looking to the Coast Salish people. It also means allowing another way of knowing the world to permeate our understanding, and open ourselves up to becoming naturalized to a place our ancestors did not steward. We are re-membering ourselves.

|

Each person, human or no, is bound to every other in a reciprocal relationship. |

Expanding the list of “Culturally significant” plants

Keystone Species: |

When we were handed a list of 15 “culturally significant” plants by the NRCS, we knew we needed to expand the list in order to achieve the diversity necessary for the Miyawaki Method. We also knew that, from an indigenous perspective, a “culturally insignificant” plant does not exist. Based on the understanding that ecological restoration requires restoration of relationship, we had a desire to approach working with an indigenous consultant in reciprocal collaboration, not transaction or exploitation.

|

Through a mutual acquaintance we were connected with Linzie Crofoot (Tlingit and Haida Tribes Center Council member, Colville-Okanagan descendent), an indigenous educator at the NW Indian College and Tayna Greene (Tulalip Tribal Community Member, Snohomish, Sauk-Suiattle, and Colville-Wenatchi descendent) her (then) undergrad student and colleague at the Naa kaani Native Program. Tayna and Linzie not only helped us to expand the list of plants, but brought our community an expanded understanding of what ecological restoration means. They taught us that restoration is not truly restorative if it does not include building authentic relationship with the indigenous people of the land you’re restoring. Humans are a keystone species.

|

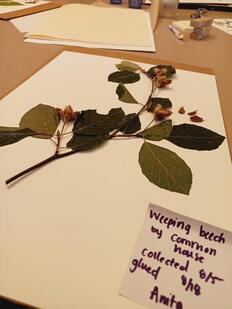

Linzie and Tayna compiled information on the cultural significance of more than 35 plants, and taught us that the plants endured and are enduring the same oppression as the people. Their plant relatives endured and are enduring the same cultural genocide as the native peoples. We learned that a piece of restoring our relationship to the land is calling the plants by their original names. In our region, that means learning and using the Lushootseed names.

Linzie chose five of the plants we were including and gave us a talk on the cultural significance of those five. Linzie’s talk: https://youtu.be/qPhxI3VzTJ0

|

Our Neighborhood Networking - The University of Washington, Bothell

|

When something wants to emerge there are often other energetic connections that pop up - sometimes they seem like they are sheer coincidences and other times they emerge from earlier collaborations. Anita has been nurturing a relationship with the University of Washington Bothell campus Sustainability Program for several years. Early in the year, Professor Amy Lambert called to ask if we might have a project that some of their students could engage in to earn their practicum hours for 2022.

The area of the planting was approximately one-sixth of an acre and covered with opportunistic weeds and blackberries. We decided to prepare the land we would dig out the blackberries and turn the sod upside down, cover it with coffee bags and several inches of mulch to allow the grass to die and begin to decompose. This was going to require a lot of physical effort. We offered our project to the students and were delighted to welcome four highly motivated students currently studying restoration. Each of them expressed that they were up for the hard work entailed in restoration. |

Preparing the Ground

|

Chickens We experimented with using our chickens to turn up the soil. We created a 10’ x 10’ pen and let the chickens work the soil for several days. However the depth of the grass prevented them from doing effective work so we resorted to turning the soil over with a large broad fork. Biochar Another thought was to improve the soil by adding biochar. We spent two days burning wood to create biochar. We inoculated the biochar with a compost tea made with mycorrhiza from the forest. We have however, decided to wait until this spring to spread a layer of biochar in the meadow. Jim Soil Another unexpected amendment to the soil was offered when a friend’s husband passed away. She had been pondering how to return his body to the earth in the most earth-friendly way. A recent law in Washington has allowed for the composting of human bodies. The process is surprisingly quick and produces a lovely compost free of toxic ingredients. When the process was complete she received a cubic yard of beautiful rich compost that we planned to use in the planting process. |

Creating the Planting Design & Sourcing the Material

|

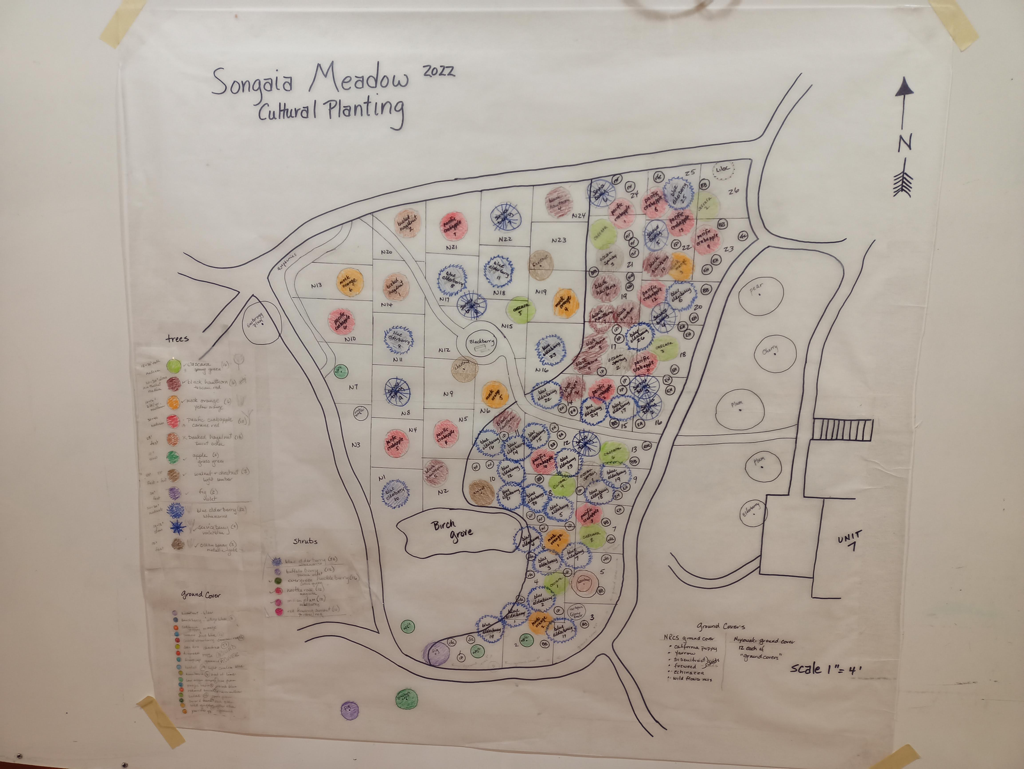

Once we had a robust list of the plants we wanted to include we began to create the planting plan and source the material. We divided the area into two sections, one to follow the densely planted model of the Miyawaki method and the other to plant according to the requirements of the NRCS. This would allow us to compare the effectiveness of the methods over time. We divided the meadow into 34 sections approximately 10' square. The Miyawaki method called for approximately 25 plants per 10' area, the NRCS required only one.

Calculating all of the plant material we would need more than 400 plants! After determining how many of each of the the plants we would need, we began to look for sources. |

We started with the conservation district plant sales, purchasing as much as we could through these low-cost sources via their on-line ordering system to be picked up later in the year closer to planting time. Then we began to look to the native plant nurseries near us for the rest.

Here are a few of the sources we used:

Here are a few of the sources we used:

|

We sourced a few plants by gathering them from the local forests. You can get a permit through the Forest Service.

Here is a list of Native Plant Nurseries in our neck of the woods: In Snohomish County In King County |

We also began propagating a large number of the ground cover plans such as yarrow and decided to include a number of the ground covers in the NRCS sections. We seeded a northwest meadow mix in several sections after removing the buttercup.

Deepening Relationships

|

As the project continued, it was obvious that deeper relationships wanted to emerge from our collaborations.

|

Watch Linzie’s lecture on

Cultural Keystone Species |

Or check out Linzie and Tayna’s book

“Our Plant Relatives” |

|

- Linzie’s mentor Lisa Powers became interested in the project, and offered to hold a ceremonial space to close our planting weekend.

- The UW Bothell Environmental Science Capstone class visited the site with professor Amy Lambert.

|

In addition to the information provided with us from Linzie and Tayna, we found a number of helpful resources, linked here:

|

Planting Event - Festival of the Earth

On the first weekend in May, in concert with the annual Songaia Festival of the Earth, we planted over 400 native plants in the former meadow. Over 75 people volunteered over the course of 3 days to transform that meadow into what we now call the Native Forest Garden. We worked, sang, laughed, sheltered from the rain, celebrated, and ate together. We acknowledged the ancestors of this land. It poured down rain, sleet and hail for much of the weekend!

Local song family Earth Practice led a song circle on Saturday evening.

To close the weekend Linzie, Tayna, Lisa Powers, and her daughter Bibianna held a ceremonial space to give gratitude to the plants, the people, and the land.

Ongoing Care

Year 2 : Winter & Spring

|

|

The first sign of spring life - the camas and nettle re-emerge (look closely).

Year 2: Summer and Fall

|

The questions we continue to ponder have begun to be answered in the project. Those questions are:

|

|